POP Stars

Duke ECE's lauded Professors of the Practice—POPs—have a passion for teaching and a mission to engage more students in the joy of engineering. Meet three of these engineers whose research focuses on education.

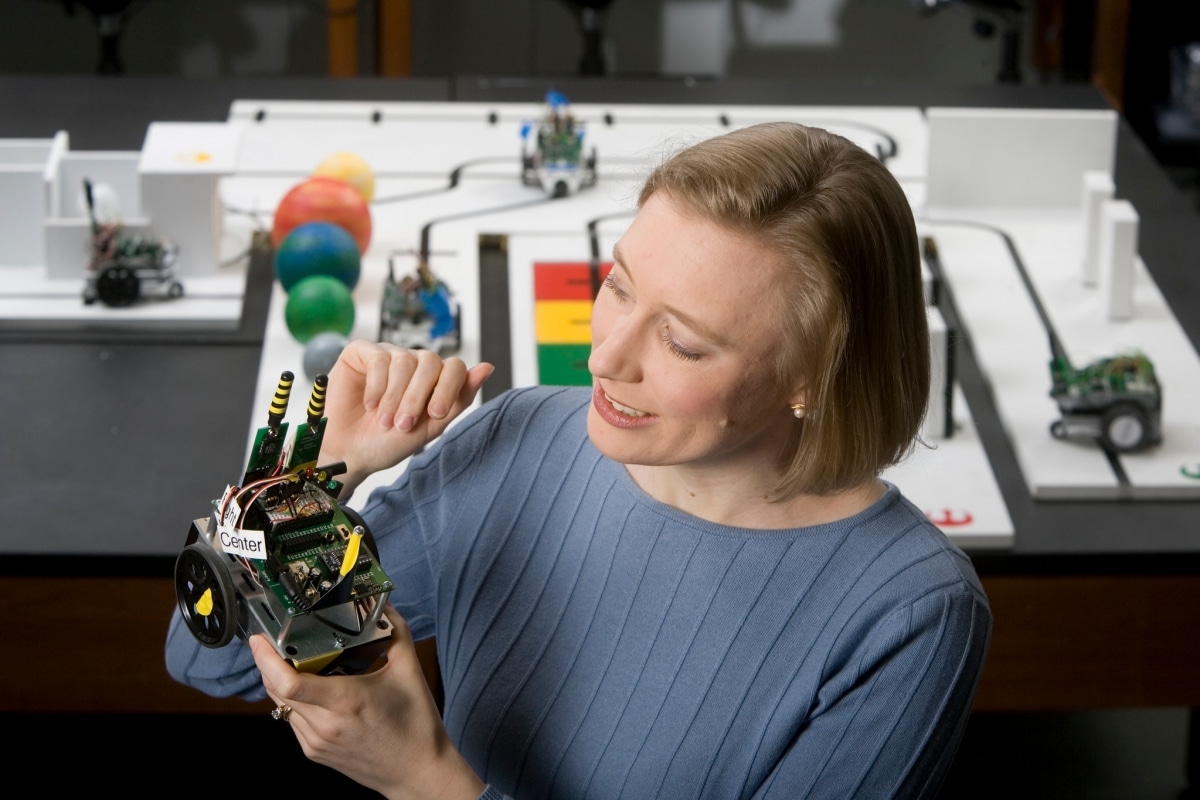

Lisa G. Huettel: Engineering Engagement

Lisa G. Huettel is the Edmund T. Pratt, Jr. School Professor of the Practice of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and the winner of the ASEE ECE Division Distinguished Educator Award in 2021, the ASEE Southeast Section Outstanding Teaching Award in 2021, and the IEEE Undergraduate Teaching Award in 2019.

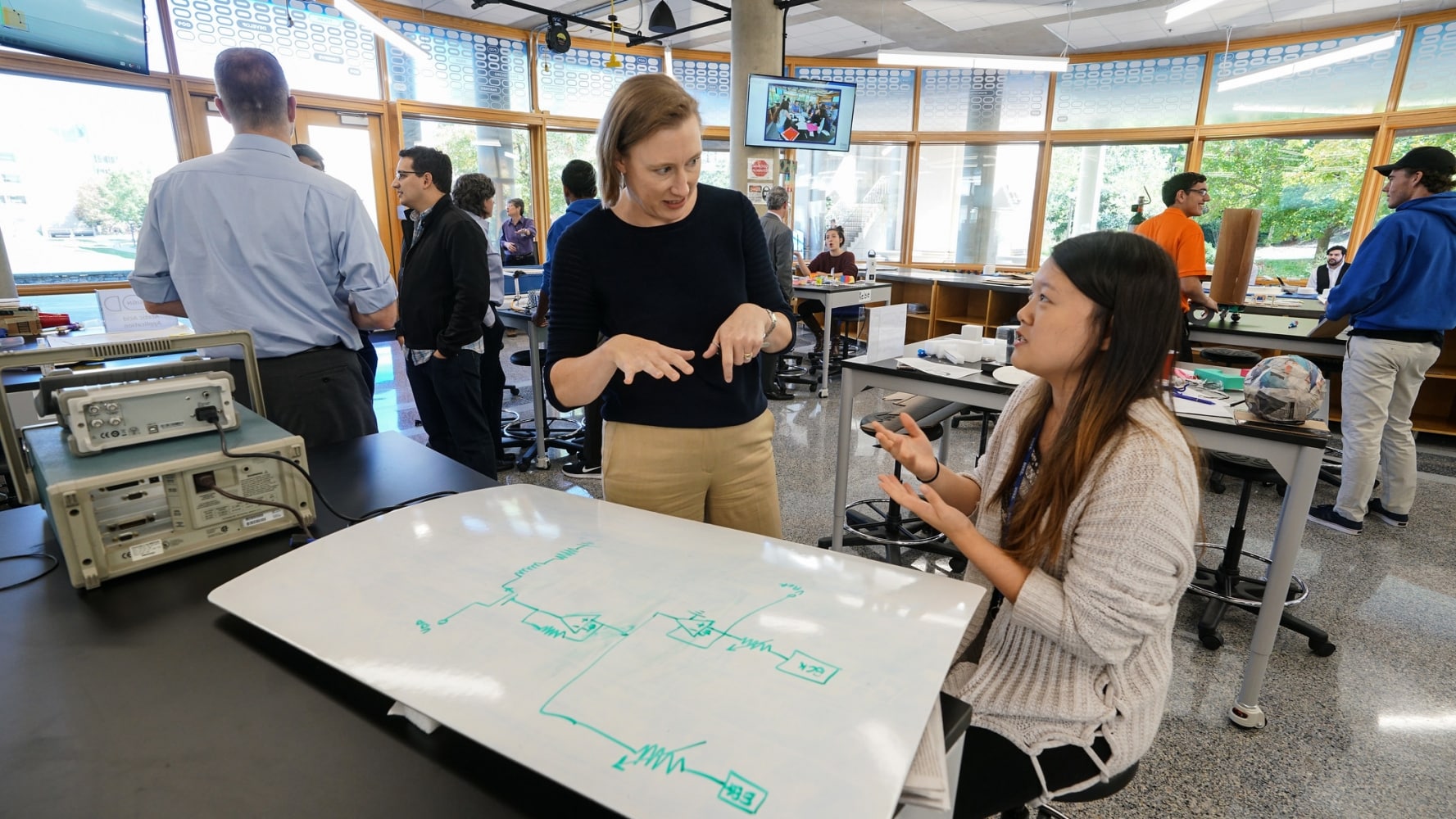

Huettel coordinated the transformation of Duke’s foundational ECE courses, employing team-based design challenges. The new format gave students the opportunity to start developing a skill set extending beyond content knowledge, and the change positively affected interest, engagement and retention. Later, when Duke Engineering reimagined its entire first-year experience, Huettel’s course was held up as a model, and her success influenced how design, computing, and statistical thinking and decision-making would be taught across the school.

Teaching philosophy:

ECE is everywhere and ECE is connected to everything. We don’t live in silos, and engineering is not isolated. We can’t therefore just be technically competent. Engineers have to know how to work in teams with other experts, how to ask questions, and how to approach and solve problems. And engineering educators have to show the relevance of ECE and choose challenges that engage students and show them the larger context.

Favorite topic to teach:

Whatever it is I’m teaching right now! I’ve revamped ECE 110: Fundamentals of Engineering, which is a required course, and ECE 381: Digital Signal Processing, which is an upper-level elective, and I am very attached to both. What excites me most with 110 is that students aren’t yet thinking in a restricted way. It’s a lot of fun to discover alongside them and watch them really dig in deep to solve lab-related projects. In the upper levels, it’s about getting to know each individual and discovering what it is that each wants to do and helping to facilitate that. Underwater acoustics, economics, sound engineering, land mine detection—all that comes back to signal processing.

When did you decided you wanted to focus on teaching?

When I was a little kid, my best friend and I loved school so much we were going to start our own school. Back then, I wanted to teach kindergarten. When you get to college you really start thinking about what you want to do, and I knew I wanted to get my PhD— I wasn’t done with learning. When I got to Duke for graduate school I TAed as much as I could. I loved it. It reconfirmed my desire to teach. At that time, the thought around the scholarship of teaching and learning was evolving, and I was fortunate that the opportunity opened up to have a career at a university like Duke, where I could focus on teaching. It just felt right. This job does not feel like work to me—being with the students is such a rewarding thing.

Shaundra Daily: Expanding Participation

Shaundra “Shani” Daily is a co-PI on two major new grants: INCLUDES is a five-year, $10 million grant from NSF to increase computing entry, retention and degree completion rates of students from historically marginalized groups, and Athena seeks to develop next-generation mobile networks and make edge computing accessible to more users.

Teaching philosophy:

The tradition I come out of is constructionism, which is the idea that students learn best when they not only have opportunities for hands-on creation of personally meaningful ideas, but also opportunities to communicate those ideas to the external world. Most of the things I design—whether a curriculum, a program or a technology—actively engage students with opportunities to create, and to present what they’ve created to an audience who can push the work forward.

Tell us about your research in diversity in STEM.

For a number of years, I’ve worked to address the question ‘How can diverse groups work together to develop computing solutions for the world’s most pressing challenges?’ A lot of my work has been in developing either technologies or programs that broaden participation. For example, I had an NSF grant a few years ago supporting the development of a virtual environment that we could use to teach programming concepts through dance. And I am the Faculty Director of Duke Technology Scholars, a program that seeks to recruit and retain underrepresented people in tech, by offering professional resources and strong support networks.

How does your expertise in this area inform your work on INCLUDES?

The INCLUDES project is led by Duke Computer Science Professor of the Practice Dr. Nicki Washington, who serves as PI. INCLUDES grew from Dr. Washington’s work combining social science and computing as well as the Cultural Competence in Computing, or ‘3C’ program, that we developed in the fall of 2020. There were 144 participating educators from six countries in the program’s first cohort. Participants read materials that we felt were important, like Race After Technology, Algorithms of Oppression, and Weapons of Math Destruction. These texts explore problems that result from not considering race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, religion, and ability and disability when developing new technologies. Then we invited guest speakers and had discussions about identity. The goal was for educators to develop modules or courses with an intentional focus on the role of identity in their practices, policies, and course content.

“If you’re teaching a course about AI, are you also teaching your students about bias? How do you examine issues of data—where it comes from and how it’s used?”

If you’re teaching a course about AI for example, are you also teaching your students about bias? How do you examine issues of data—where it comes from and how it’s used? Similarly, how are your course policies potentially harmful to students? Are you disadvantaging students from certain groups?”

What’s your role in Athena?

I’m leading the Educational Workforce Development thrust of Athena, thinking about education all the way from kindergarten through the postdoctoral level, and about how to diversify and broaden participation.

In the K-12 sphere, I’m working with Daniel Limbrick at North Carolina A&T University, who runs a successful robotics program, to implement industry tours and letting students see more applied engineering projects. Athena deals with AI on the edge, so it’s helpful to see use-inspired research, like in the autonomous vehicles space—to answer the question, “Where does the research go in the real world?”

In higher education, we want to make sure students have options for class projects, capstones and master’s projects that focus the research thrusts and continuously consider ethical questions related to their work.

Rabih Younes: Interfacing with Industry

Teaching philosophy:

I try to provide a class experience where students retain knowledge for the long term while making connections to real-world applications and developing life-long learning skills. My teaching is mostly based on research in education (especially engineering education), neuroscience and psychology. Using my theoretical knowledge about how brains work, I use techniques and tools that help maximize the students’ retention of what they are learning, and I reenforce that knowledge with activities, projects and homework that are at a challenging sweet spot which triggers their motivation and curiosity.

I also keep in mind that different students take the same course for different reasons, so I always try to give them the opportunity to realize their goals, however different these goals might be. Furthermore, I often have discussions with them about the impacts of their work, especially ethical impacts, and other big-picture philosophical discussions that relate to their future and push them to be better critical thinkers.

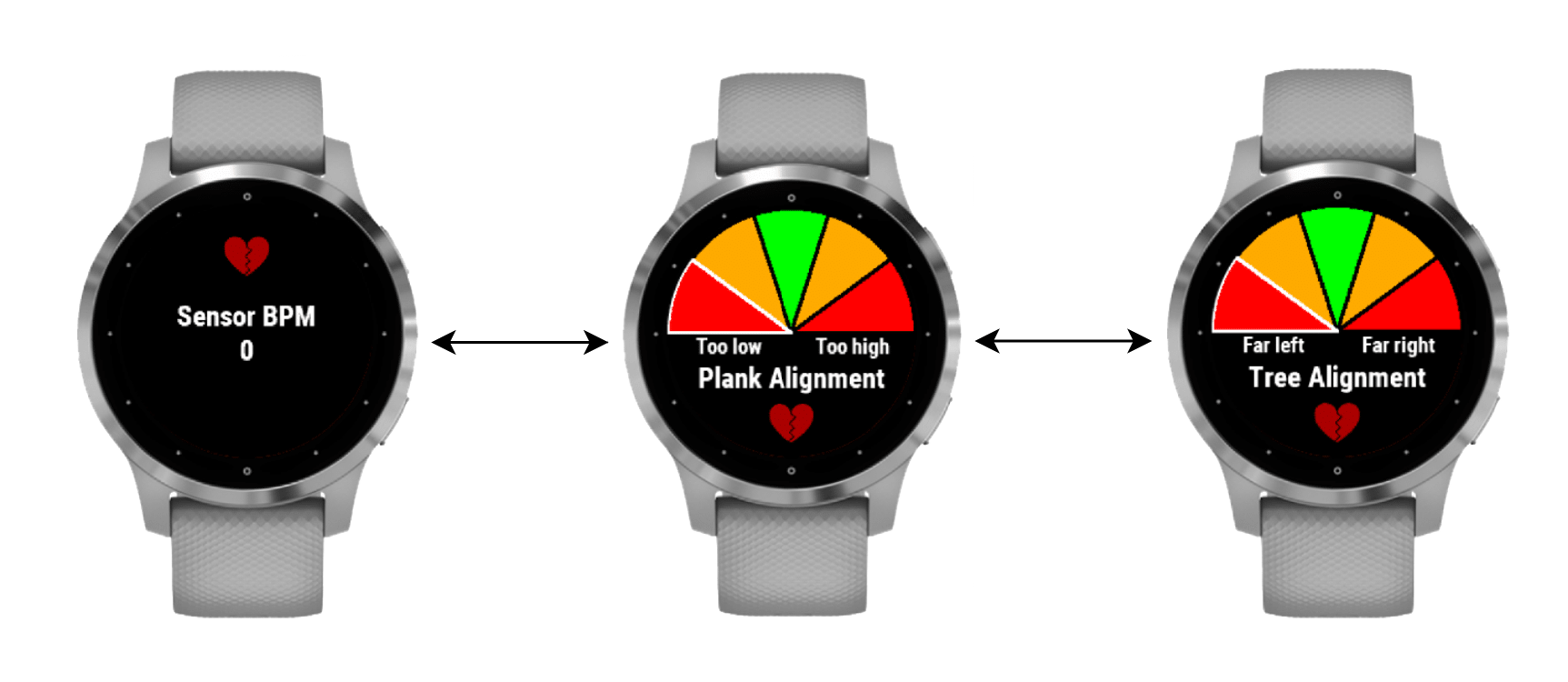

Your senior design class on wearables offers the opportunity for students to collaborate with an industry partner. What do the students get from this collaboration? What does the industry partner get?

Garmin was the first industry partner I collaborated with in my wearables course two years ago. After seeing how well this went and how much students benefited from this experience, I am planning to expand the number of industry collaborators next semester. Through these industry experiences, students get to interact with a real client, which is the best way for them to prepare for their future jobs. Through the industry partnership, students also get to develop a prototype or product that real people will end up using, which is definitely motivating. As for the industry partner, they get new approaches to product development, and the chance to build real connections with potential future employees.

When did you decide that you wanted to be an educator?

I first started tutoring my peers in school when I was about 14 years old. After a while, I noticed that I was good at it and needed to make some money, so I started working as a paid tutor and had many students. By the time I was in grad school, I had taught K-12 students, college students, and I was an instructor trainer at the Cisco Networking Academy. That experience made it very clear to me that I want to be a professor, which pushed me to take courses in education and engineering education along with the courses required to complete my PhD in Computer Engineering.

What are your favorite classes or projects to teach, and why?

My favorite class to teach is my ‘Wearable and Ubiquitous Computing Systems Design’ course, which I currently teach every spring semester. It is a senior design course where students work in interdisciplinary teams to develop wearable computing systems that address real-world needs and add value for users. They learn about wearable and ubiquitous computing, but also how to work effectively in teams and how to manage a big project. I really like this course because I get to interact with a small number of students while sharing with them everything I know about wearable and ubiquitous computing–knowledge I’ve acquired through years of research. Plus, the tasks are very hands-on, which is definitely a lot of fun.