‘Embrace the Ditch,’ and Other Lessons Learned in Duke CEE’s Overture Engineering

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

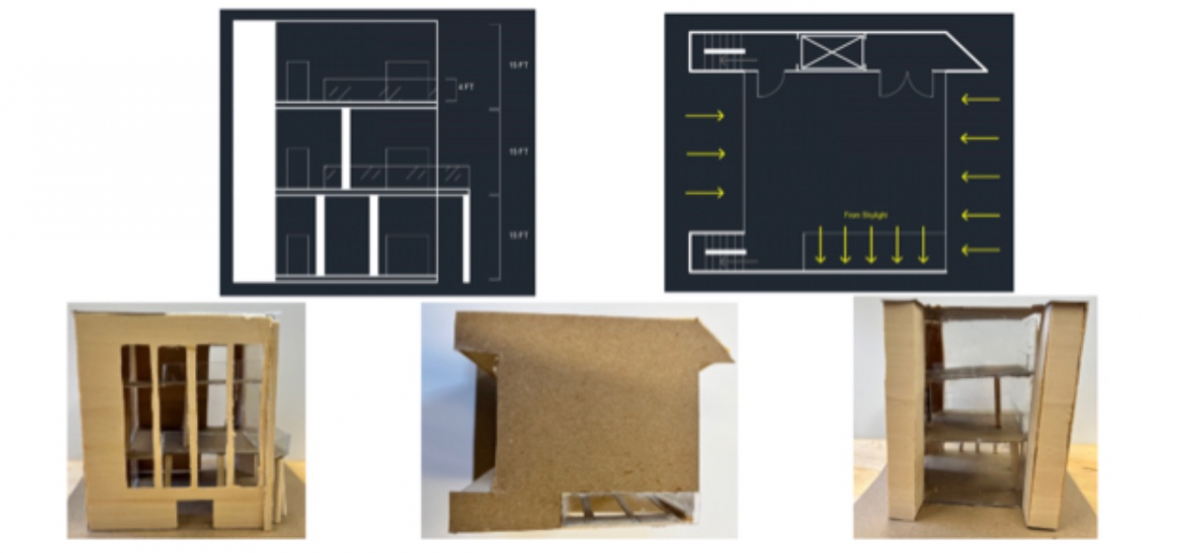

For an assignment in Architectural Engineering I, Duke civil and environmental engineering student Jessica Wey designed a pavilion. She enjoyed the creative freedom she had in imagining the building’s form, how natural light might help illuminate the structure, and what kind of land the structure might occupy.

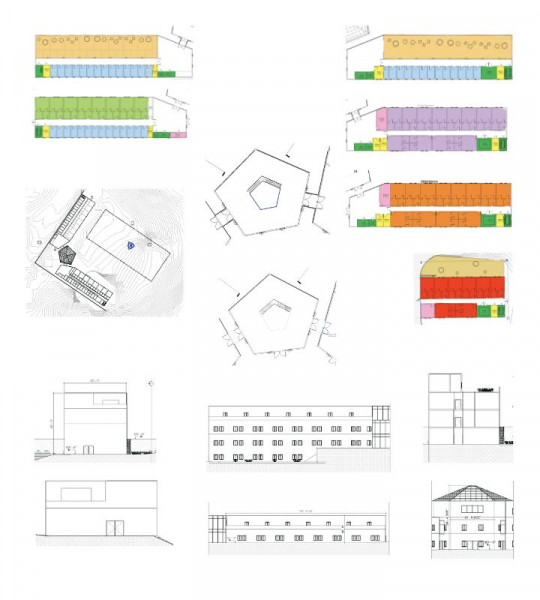

In Architectural Engineering II, she was again asked to design a building. This time, however, some choices had been made for her: the building would be used for scientific research and it would be located on a predetermined plot located on Science Drive and Towerview Road.

When she first laid eyes on the steep, wooded slice of land alongside Gross Hall that was the theoretical building site, she knew this would be a very different kind of design experience.

“The site was in a big ditch,” she said. “Our class tried hard to get it changed.”

But her instructors remained firm in their choice.

“People in fields like ours are used to being able to work a problem set and arrive at an answer in which we have 100% confidence,” said Chris Brasier, who directs Duke’s Architectural Engineering Certificate and is an adjunct CEE professor. “In real-life situations like these, though, we want to demonstrate the tradeoffs at play. Avoiding undesirable topography could force a building to assume a taller shape. How, then, does that fit with surrounding buildings? Or, if the team designs a low, flat building, does it then encroach into environmentally sensitive areas? The students do have to struggle with the problem a bit.”

Brasier’s course—CEE 411: Architectural Engineering II—is one-third of a cooperative simulation of engineering practice known as “Overture Engineering.” The other two-thirds comprise civil and environmental engineering capstone courses led by professors of the practice of civil engineering Joseph Nadeau and David Schaad, both of whom are PEs—licensed professional engineers.

“The idea is to introduce students to the collaborative nature of practice, which is rarely a solo act.”

Chris Brasier, FAIA, LEED AP, MBA | Duke Architectural Engineering Certificate Program

“The idea is to introduce students to the collaborative nature of practice, which is rarely a solo act,” said Brasier, a practicing architect since 1988 and an instructor at Pratt since 1996.

Brasier’s students walk the chosen site in this course and make observations as a precursor to the actual design phase. They translate their insights into visual analyses—a series of diagrams noting factors like pedestrian circulation or traffic flow, vegetation and topography. After careful consideration, each student develops three different approaches to how a new research building could occupy the site.

“We pin up the designs, talk about them, and converge on solutions that we think strike an optimal balance,” said Brasier. The students are then sorted into three teams, each charged with creating design plans that will be passed to Nadeau’s structural capstone class and then to Schaad’s environmental capstone class.

“The design varies from team to team, so the challenges also vary. The structural teams have to consider changing column loads when a building gets taller, for example. And a large footprint might cause stormwater and drainage issues for the environmental team,” explained Brasier.

Wey is enrolled in Schaad’s environmental engineering capstone and Brasier’s architectural engineering class, so she was invested in creating a design that would be easy to implement down the road without making her job as an architect more difficult.

Her team decided, therefore, to situate its building on a nice flat portion of the site, facing the Law School, only to realize later that the design didn’t meet the minimum square footage the project required.

“We had to design a second building, and we had to place that building in the ditch,” said Wey ruefully. “I heard it was one of the hardest designs to inherit.”

Duke CEE graduate Rachel Fleming ’12, ’13 remembers her experience in the department’s capstone and the feeling she got when being presented with her design sketches.

“All of a sudden, you’re introduced to a broad project with so many different components,” she said. “It can be frustrating when you’re introduced to all of it at once, but it really does mimic the layers of complexity you’ll encounter in a real-world project and prepare you for that experience.”

Fleming, a project manager at owner’s representation firm MBP, now handles everything related to building and facilities projects, from the earliest design phases through the final punch list.

“I felt like the capstone provided a glimpse of how specialties have to work together to communicate and share information.”

Rachel Fleming ’12, ’13 | Project Manager, MBP

She said the communication skills she honed during the capstone were immediately transferrable to her profession.

“I felt like the capstone provided a glimpse of how specialties have to work together to communicate and share information,” said Fleming. “For example, if we wanted to clarify design intent—what the architects were envisioning the space to be—we’d have to file a formal Request for Information, or RFI, like a contractor would in the real world.”

The value of some other course requirements, like submitting timecards for the project, were helpful only years down the road.

“Now, when I’m helping develop fee proposals, I have to think about the task, the level of effort, and how long it’s going to take,” said Fleming. “That’s how you bid a project or submit a fee proposal.”

“It was definitely a learning experience,” agreed Wey. “What my team learned is that trying so hard to work around extreme topography made the problem more difficult. In the future I’d work with it instead of around it, which could actually lead to some cool designs—some overhangs, or some interesting leveling or terracing going on.”

Wey will get plenty of future opportunities—she’s starting a graduate program in architecture in the fall, after she leaves Duke with her Certificate in Architectural Engineering in hand.

And she has some words of advice for future students: “Embrace the ditch,” said Wey.