‘Embrace the Ditch,’ and Other Lessons Learned in Duke CEE’s Overture Engineering

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

We’re sorry, but that page was not found or has been archived. Please check the spelling of the page address or use the site search.

Still can’t find what you’re looking for? Contact our web team »

Read stories of how we’re teaching students to develop resilience, or check out all our recent news.

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

On a Star Wars-themed field of play, student teams deployed small robots they had constructed

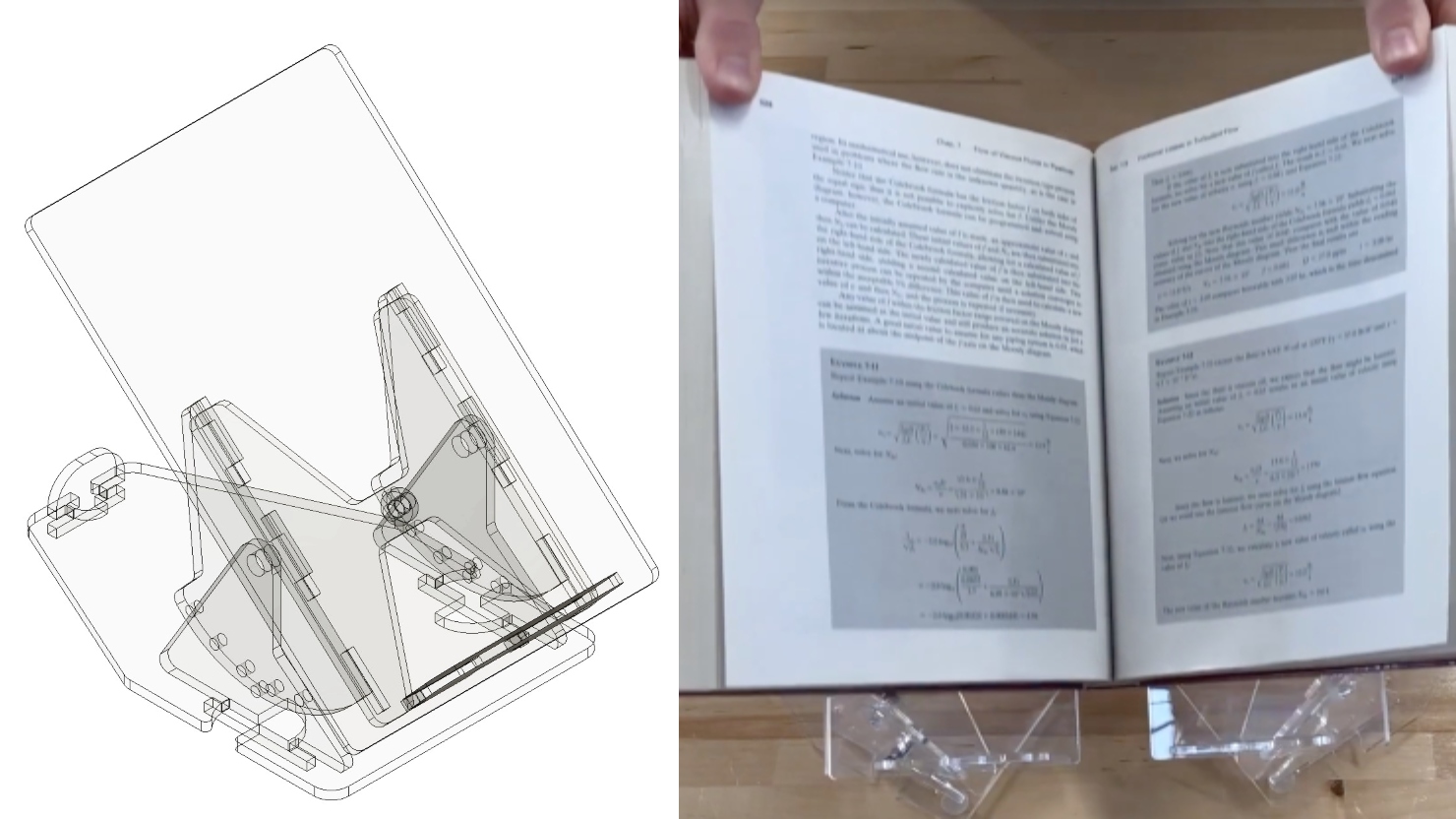

Two projects from First-Year Design course are patent-pending. Student surveys suggest the course also fosters teamwork, leadership and communication skills.

Jul 7

Jul 9

Jul 10

Come cheer on competitors as they deliver their 3-Minute Thesis presentations. Judges will determine who from this round moves on to the Finals!

10:00 am – 10:00 am Teer 115