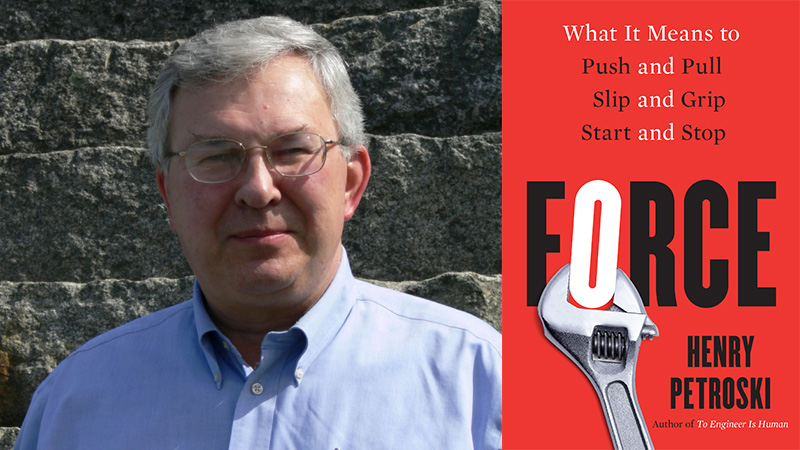

Petroski Pens Book on Forces at Play in Everyday Life

Force: What it Means to Push and Pull, Slip and Grip, Start and Stop is Petroski’s 20th book about science and engineering written for a general audience

Henry Petroski, the Aleksander S. Vesic Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Duke, is renowned for conveying the wonder of physics and engineering to readers from all walks of life. His new book Force: What it Means to Push and Pull, Slip and Grip, Start and Stop, published on September 20 by Yale, explores the amazing forces at play as humans interact with the world every day.

With vividness and insight, Petroski reveals the forces that underlie our experiences when we use a pencil, visit the supermarket, wear a mask, hug each other, lie on a bed of nails, cross a bridge, and so much more. What forces are at work when a cat hangs from a door handle to open a door? How much weight can a single human hair bear? How about a whole head of hairs? Why might troops marching in lockstep across a bridge endanger it? How many people does it take to move an Egyptian obelisk?

Written for anyone with a curious mind, the book also considers the significance of force in shaping societies and cultures. The story of human ingenuity and invention across millennia is a story of harnessing and putting to use in new ways the physical forces that define our world. From cooking to building to seafaring to farming to traveling to planting—beneath every aspect of human culture everywhere is the management and exploitation of force.

Petroski responded to our questions about how his new book came to be and what he learned while writing it.

What inspired you to focus on the concept of force in our daily lives?

Forces are ubiquitous but go mostly unnoticed, even though we rely upon them in carrying out our everyday activities. This “invisible out in the open” quality of force is exactly the kind of topic that I love to explore. Every time we touch someone or something, force is involved and the sensation tells us something about the subject of our interaction. Think of shaking hands. Some handshakes are firm, others flaccid. Our first impression of a person often depends on how much force is transmitted through the grip that we experience in shaking hands. And think of how we handle inanimate things. We grasp some things with much greater force (more firmly) than we do other things. This is something we must learn, for a child does not know innately to press much less hard in picking up an egg than a rock. We have to learn what forces are appropriate for what circumstances.

There are so many forces at work in our daily lives; how did you choose specific examples on which to focus?

There does seem to be an almost unimaginably large variety of ways in which force manifests itself, but virtually all of them can be understood in terms of two basic forces: push and pull. By explaining how all forces reduce to combinations of push and pull, I provide the reader with insight into how less simple forces can be applied and reacted to most effectively. This kind of knowledge helps us more safely walk on icy sidewalks, more easily open stubborn jars of jelly, better play games involving bats and balls, and even have a better chance of winning a bet over which way a wheel will turn in response to a push or pull—to mention just a few of the activities I write about in FORCE.

Did the experience of writing this book differ from your previous books in any significant way?

Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that I could literally feel what I was writing about. For example, when I was describing the forces involved in putting on a pair of slippers in the morning, I needed to do little more than put on my slippers to check my memory of how I feel the forces interacting between my feet, the slippers and the floor. At the same time, no, writing FORCE did not differ from writing many of my other books, in that I had to do research to put the concept of force in some historical perspective and to be sure I did not rely solely on my own idiosyncrasies in describing and discussing what I claim to be universal experiences that we all have but do not always think about.

Which chapter did you particularly enjoy writing?

I should not play favorites with my book chapters any more than I do with my children. However, I have to admit that I did have fun writing about levers and inclined planes. Both of these simple machines have been known and used since ancient times, but we sometimes complicate our handling of them by not recognizing them as the ingenious mechanical devices that they are. From morning to night, we encounter levers in the form of: eating utensils, toothbrushes, gas pedals, steering wheels, brake pedals, pencils and pens, light switches, and so many of the other things we touch throughout the day. It is levers that enable us to convert one kind of force into another. My chapter on inclined planes enabled me to engage in my habit of punning. An inclined plane can be a ramp up which we are pushing a wheelchair, as well as a jumbo jet taking off from a runway and climbing at a steep angle. The forces involved in each situation are essentially the same—with gravity and inertia doing most of the pushing and pulling—and, by pointing this out, I hope to emphasize how very dissimilar activities can be the result of very similar forces.

Is there any specific force that you think has been more powerful in shaping the world in which we live than others?

If we are talking about shaping the world of made things, such as manufactured goods, I would have to return to the forces of push and pull. The Industrial Revolution depended to a large extent on the ability to pound (push) iron and steel into shapes that could be used for railroads and locomotives, and also to extrude (pull) them into a wire that could be used to support bridges and carry electricity. Today, pushes and pulls are the essential physical forces involved in making so many of the plastic products that replace parts that were once made of more easily recyclable materials such as glass and steel. And now it is pushes and pulls that have to be involved in the recycling of plastics. If we are talking about metaphorical force, then again we have to think of pulls and pushes. They are the carrots and sticks that drive our world.

During your research what were you particularly surprised to find?

Among the most surprising things I found out was that many people have less of an understanding of physical force than they do of metaphorical force. For example, although everyone seems to understand the possibility of being persuasively “forced” to do something against their better judgment, they do not necessarily comprehend how a particular physical force and a certain motion are related. Even college students who took a physics course in high school cannot be relied upon to predict which way a particular object will move when a certain kind of force is applied to it. In fact, even some college graduates do not have a sophisticated sense of force, as I confirmed through my research. I would like to think that after reading my book, people from all walks of life will have a better grasp of how force and motion are related.