Duke’s Semiconductor Game Changers: Tania Roy

Tania Roy studies novel semiconductor materials and devices to advance energy-efficient computing and edge AI.

We’re sorry—the news story you were looking for has been archived.

Please see the most recent stories below.

Tania Roy studies novel semiconductor materials and devices to advance energy-efficient computing and edge AI.

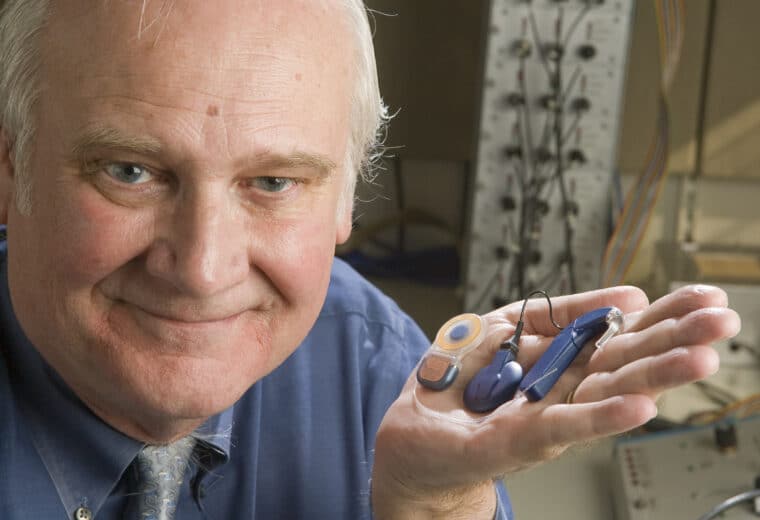

Wilson shares this prize for his contributions to the development of the cochlear implant.

Yiran Chen develops brain-inspired semiconductor hardware to enable faster, greener AI at the edge.