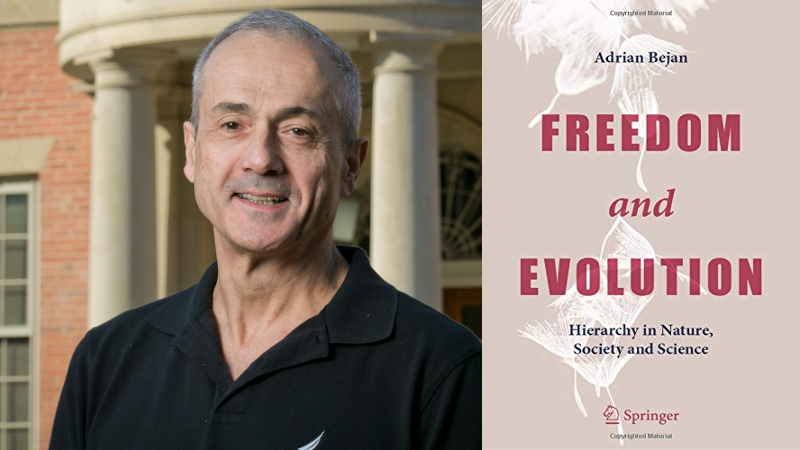

Freedom and Evolution: Hierarchy in Nature, Society and Science

Adrian Bejan has written his third book intended for a general audience centered on his concept of the constructal law

Tell us what your new book is about.

As the title suggests, the book is primarily about freedom and evolution. The book explores the meaning of these words, and also places these two concepts firmly in the realm of physics, which is the most generally applicable intellectual tool that we have in science.

Can you elaborate?

Evolution is, very simply, the changes that occur in a discernible direction in time. Freedom is the physical feature that enables an entity or system to make these changes. So no freedom, no change. No evolution. No time. No future. The remaining words in the title—hierarchy, nature, society and science—are the meat of the book and are chosen to show that these two words, freedom and evolution, in fact mean the same thing. Because without freedom you don’t have evolution, or for that matter, civilization.

That’s quite a bold statement.

But it’s a true statement! Freedom allows evolution, which in turn forms hierarchies. You can see this in nature where flows distribute themselves through a few large currents that branch into many smaller streams. A river delta, tree root system, or the capillaries in your muscular tissues, are prime examples. Civilization is no different. These same hierarchies can be seen in the evolution of urban infrastructure such as roads and water pipes, the evolution of airplane design, and the distribution of wealth and power. It is the basic tenet of the physics of evolution, which I coined as the “constructal law” in 1996.

To a mind that constantly asks how we can do things better, it’s important to know how to spread something that needs to serve an entire area. The one-size-fits-all model will never work. It is the opposite, the hierarchical flow architecture, that does the job not only most easily, but most naturally. It happens because nature has the tendency to flow—to configure itself to fill a space over time more and more easily. That is the constructal law.

Speaking of the constructal law, this is now your third book for general audiences on the topic. How does this book differ from the previous two?

These three books show the evolution of an idea toward a simpler, more direct and more memorable message. The first book, Design in Nature, was wholly descriptive and meant for the widest audience possible. The second book, The Physics of Life, was more personal, meaning that it was about you, the reader, interested in living your own life. This third book is really to answer the question: What is the essence? It puts all of these ideas into the simplest, and thus most widely applicable, form.

So walking away from this book, the reader should be able to see how evolution is a basic tenet of physics and at work in everything around them?

Yes, most definitely. When I read news that suggests evolution is 100 percent a biological phenomenon, I actually become amused. Working in an engineering school, I see evolution galore every day in this very building. And I see it in the news every day. Politics, city government or even the traffic map of Durham, North Carolina is an evolutionary design.

Evolution, from my point of view, is in the mind and spirit of everyone, and it means this—design change over time. Not random change, but change moving in a discernible direction. Randomness, or hiccups as I call them, of course happens along the way. But at the end of the day, there is a direction, and frankly that is the good news that’s worth teaching to those who wonder about the future of anything.

So yes, again, this is actually the big idea that this new book outlines. One develops a much better idea of what the future is going to be like. It’s about understanding the future of energy sustainability on Earth. The future of political stability. The future of the globe itself.

And that future is necessarily hierarchical?

In every way, shape and form. The non-uniform distribution of everything, not just wealth, will happen naturally. That’s why helping your fellow man and voluntary acts of altruism and philanthropy is a never-ending challenge, and one that I completely agree is worth taking on. But at the same time, I grew up under a communist regime and witnessed first-hand the impossibility of instituting complete equality. The catastrophe that followed was natural because of the unnatural effort to create a uniform society.

So in reading this book, stories of physics teach the impossibility of achieving these types of systems. Except I use much simpler examples, such as the stupidity of building a piping network with pipes all of the same size. But in knowing the demarcation lines between the possible and the impossible, one can create daring designs that are just a few steps from falling over the cliff. And great benefits come to those who venture that close to this cliff.

It sounds like there’s some good advice for planners and inventors in these lessons.

Indeed, there’s an entire chapter about innovation. I talk about how each of us is now a lot more than the naked ape. We are now a human-machine species that is constantly trying to improve on itself. Which, by the way, is the definition of evolution. Every time you choose a different pen, pair of shoes, or new smartphone, you’re trying to better equip yourself for tomorrow. My colleagues in biology call it niche construction for animals. And so for humans, we’re constantly building our niche through new machines, city infrastructures and social organizations.

All of these systems are very big and complex, but after reading the very simple text of my book, you begin to see them in a new, single light. As you have one ‘aha’ moment after the next, they begin to reinforce and build on top of one another. It’s much like the design of a Russian doll. When you open one, you find there are many more inside…and they’re all the same doll.

Adrian Bejan is a world leading researcher in the field of thermodynamics, having contributed numerous important and influential findings in addition to his formulation of the physics law of evolutionary design. He has written 30 books on thermal sciences, has been awarded 18 honorary doctorates from universities in 11 countries, and was awarded the Benjamin Franklin Medal in 2018.