‘Embrace the Ditch,’ and Other Lessons Learned in Duke CEE’s Overture Engineering

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

We’re sorry, but that page was not found or has been archived. Please check the spelling of the page address or use the site search.

Still can’t find what you’re looking for? Contact our web team »

Read stories of how we’re teaching students to develop resilience, or check out all our recent news.

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

On a Star Wars-themed field of play, student teams deployed small robots they had constructed

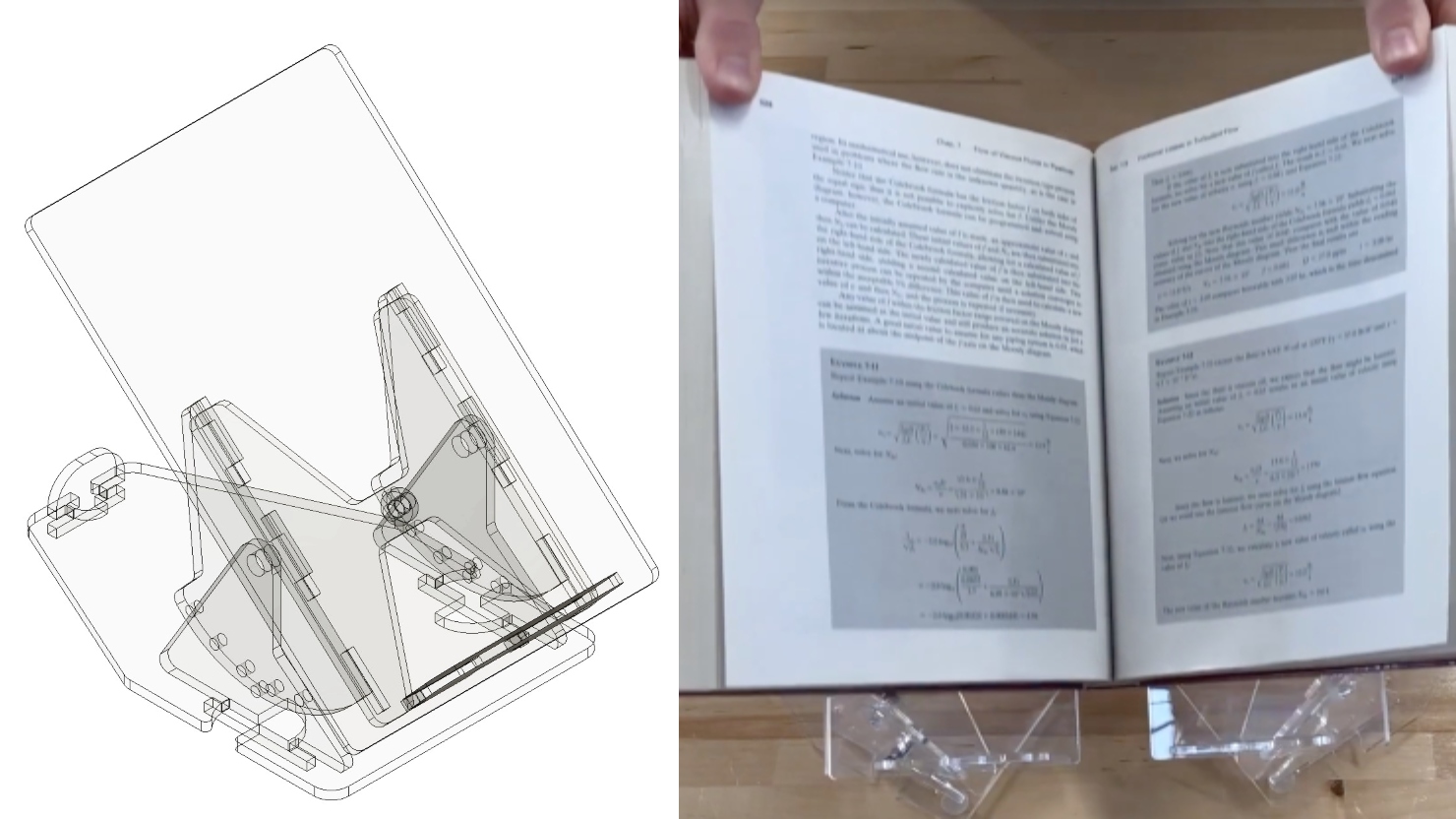

Two projects from First-Year Design course are patent-pending. Student surveys suggest the course also fosters teamwork, leadership and communication skills.

Apr 17

All engineering Master’s students are invited to use this weekday service to have an individual conversation with a career coach about any topic. No appointment is needed and the conversation […]

11:30 am – 11:30 am

Apr 17

Thomas Lord Department of Mechanical Engineering presents the PEARSALL LECTURE with Dr. Joseph DeSimone, “The Delicate Interplay Between Light, Interfaces and Design: The Complex Dance That Allows 3D Printing to […]

12:00 pm – 12:00 pm Fitzpatrick Center Schiciano Auditorium Side A, room 1464

Apr 17

We are excited to announce the next session of the Spring 2024 Computational Medicine Seminar Series featuring David Carlson. This seminar will explore “Machine Learning to Infer and Control Brain […]

2:00 pm – 2:00 pm