‘Embrace the Ditch,’ and Other Lessons Learned in Duke CEE’s Overture Engineering

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

We’re sorry, but that page was not found or has been archived. Please check the spelling of the page address or use the site search.

Still can’t find what you’re looking for? Contact our web team »

Read stories of how we’re teaching students to develop resilience, or check out all our recent news.

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

On a Star Wars-themed field of play, student teams deployed small robots they had constructed

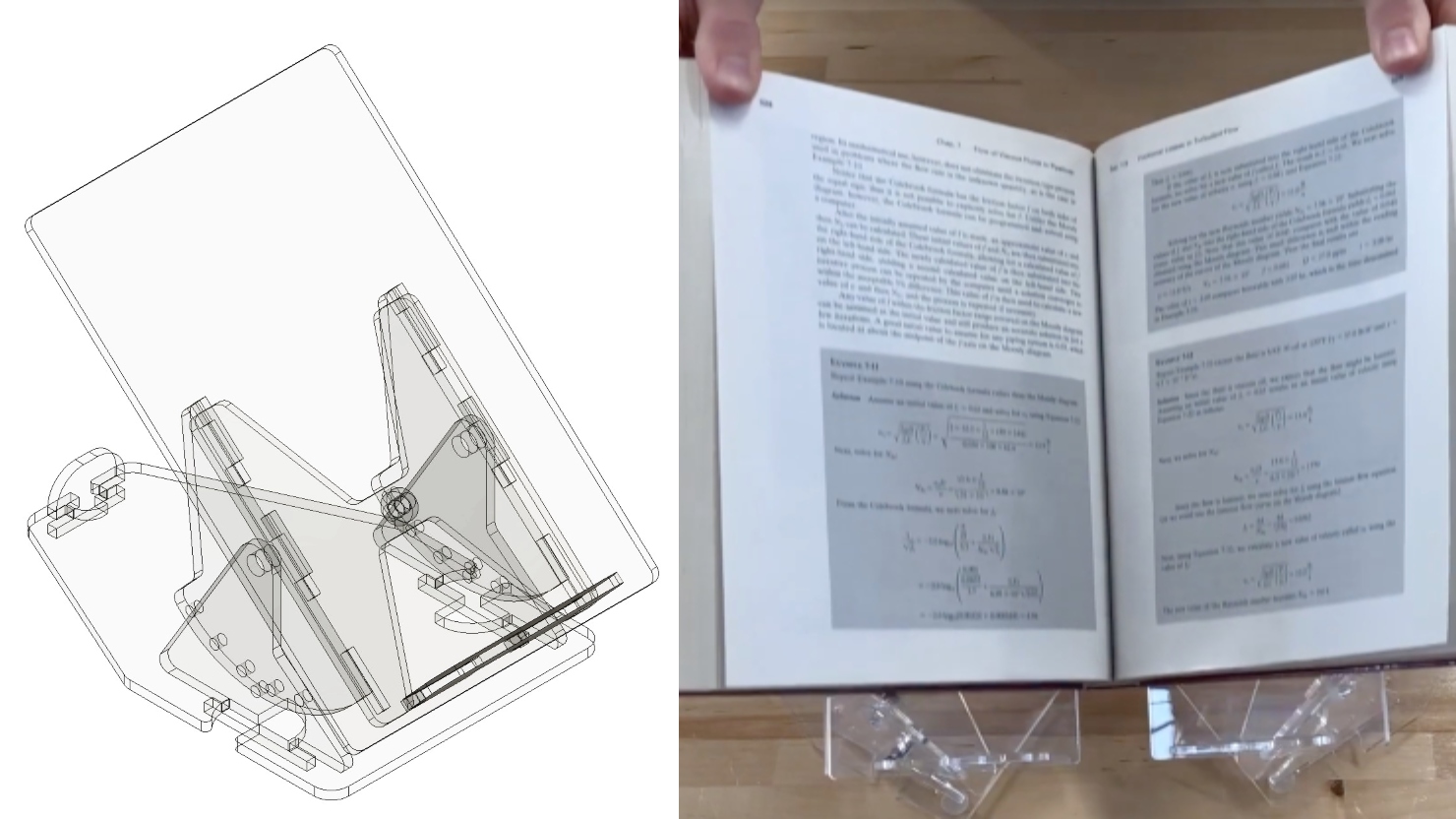

Two projects from First-Year Design course are patent-pending. Student surveys suggest the course also fosters teamwork, leadership and communication skills.

Apr 25

With host Warren Grill. Location to be announced. The goal of Hubert Lim’s lab is to push the development and translation of brain-machine interfaces from scientific concepts into clinical applications, […]

12:00 pm – 12:00 pm TBA

Apr 26

Title: How does one bit-flip corrupt an entire deep neural network, and what to do about it. Abstract: Deep neural networks are increasingly susceptible to hardware failures. The impact of […]

2:00 pm – 2:00 pm Fitzpatrick Center Schiciano Auditorium Side A, room 1464

Apr 26

Get ready to dive into the realm of creativity and innovation at Pratt’s annual student design fair! Swing by the Wilkinson Building on West Campus on Friday, April 26th, from […]

3:30 pm – 3:30 pm Wilkinson Building Plaza