‘Embrace the Ditch,’ and Other Lessons Learned in Duke CEE’s Overture Engineering

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

We’re sorry, but that page was not found or has been archived. Please check the spelling of the page address or use the site search.

Still can’t find what you’re looking for? Contact our web team »

Read stories of how we’re teaching students to develop resilience, or check out all our recent news.

Civil and environmental engineering students learn to design buildings within less-than-optimal parameters in a collaborative capstone course

On a Star Wars-themed field of play, student teams deployed small robots they had constructed

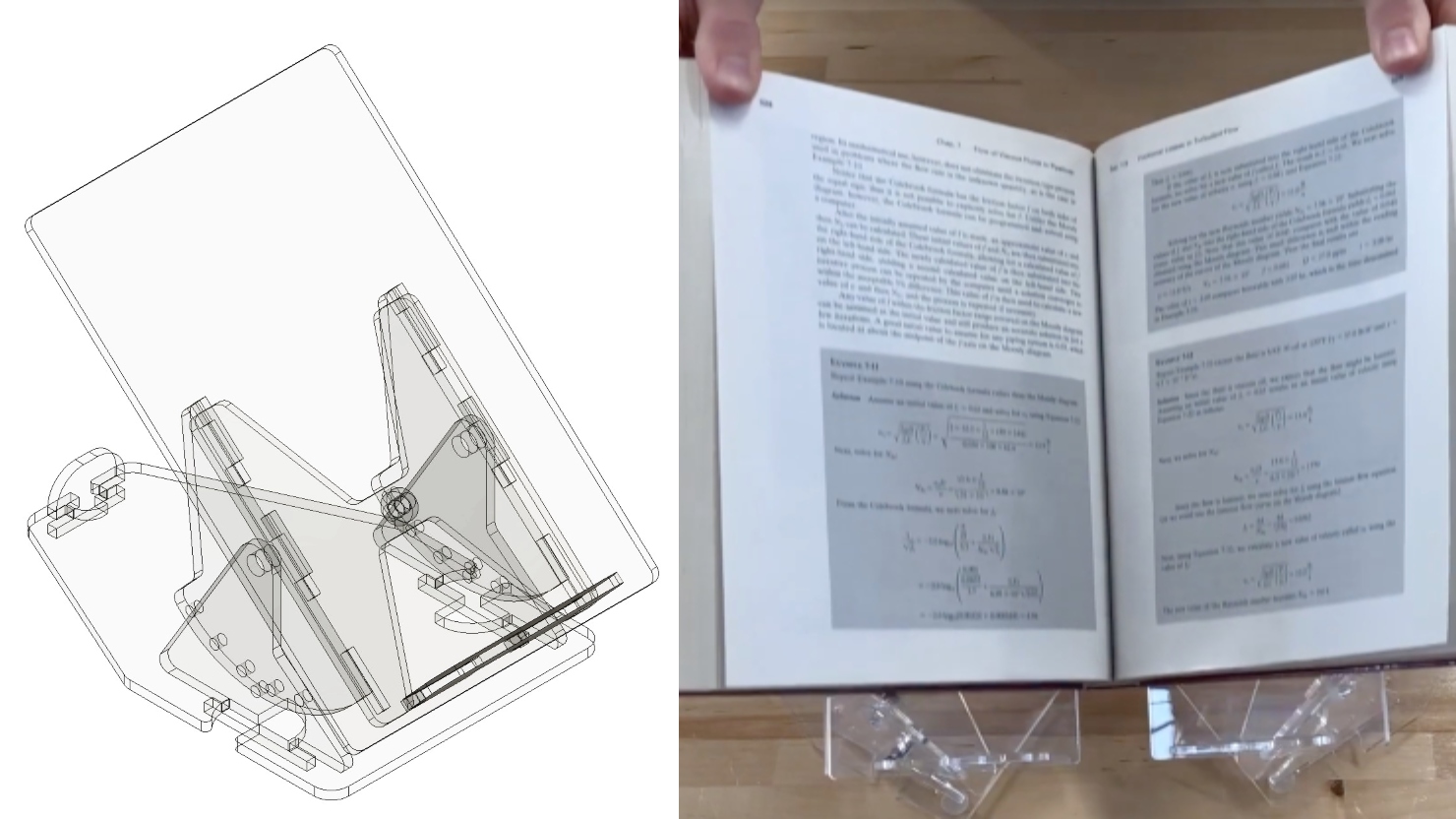

Two projects from First-Year Design course are patent-pending. Student surveys suggest the course also fosters teamwork, leadership and communication skills.

Apr 19

Teaching practice, just as any other scholarly activity, is an area about which you can form questions and hypotheses, gather data, and iterate based on the results of your study. […]

12:00 pm – 12:00 pm Virtual

Apr 19

Microplastics, particularly nanoplastics, are widespread contaminants, virtually present in all engineering and environmental systems. Also abundant in these systems are biofilms, or bacteria surrounded with extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to […]

12:00 pm – 12:00 pm Fitzpatrick Center Schiciano Auditorium Side A, room 1464

Apr 19

Microplastics, particularly nanoplastics, are widespread contaminants, virtually present in all engineering and environmental systems. Also abundant in these systems are biofilms, or bacteria surrounded with extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to […]

12:00 pm – 12:00 pm Fitzpatrick Center Schiciano Auditorium Side A, room 1464